Genomics Standards on the Danube. GigaScience at GSC21 in Vienna

The 21st meeting of the Genomics Standards Consortium (GSC21) took place last week in Vienna at one of the oldest universities in the world – the University of Vienna – from May 20th-23rd. We’ve been long time supporters and participants of the Genomics Standards Consortium meetings going back to 2012’s GSC13 in Shenzhen, and have also published a special series of GSC “Best Practice in Genomics Research” papers. As a member of the board of the GSC, GigaScience Lead Biocurator Chris Hunter was present. The rain and drizzle didn’t put a dampener on the proceedings with around 80 delegates from all over the globe coming together to discuss not only the standards themselves but also the implementations and achievements of those using them.

Genomics Standards Consortium (GSC21) conference attendees. Photographer – T Rattei & team. Source – GenSC.org.

Shedding light on Dark Microbes

Keynotes from distinguished speakers rounded off each day of GSC21, with Phil Hugenholtz (University of Queensland, Australia) kicking of the meeting with the opening keynote on the Genomic Taxonomy Database (GTDB). This resource attempts to categorise all (sequenced) life by phylogenetic relationship. Its primary focus are micro-organisms that cannot be readily categoriszed by more traditional phenotypic means. The newly developed GTDB-toolkit allows users to effectively place their own “dark microbes” within the phylogeny to gain insights into which clades are represented in their environmental sample(s).

Phil Hugenholtz highlights the role of the Genomic Taxonomy Database. Photographer – T Rattei & team. Source – GenSC.org.

OMIC Observatories: the need for better standards

Tuesday morning started with the current GSC chair, Lynn Schriml (University of Maryland, USA), giving an overview of the GSC and its history. Lynn was followed by another GSC board member, Nikos Kyrpides (DOE-Joint Genome Institute, USA) who presented his own personal views on the current state of unrestricted open access to public genomic data. This led to lively discussions on the hot topic of licenses and how to make them more transparent to users of the INSDC and other archives.

Before the coffee break Pier Buttigeig (MPI Bremen, Germany) gave the low down on the current situation with the growing body of “OMIC” observatories, and the need for better defined standards in this area. Pier reported there are difficulties due to a lack of a central registry. Pier highlighted the issue in the context of a marine survey. As one means of addressing this issue, Pier highlighted a global oceans survey that generated a list of 71 potential marine observatories. Nikos added that there are various other networks of environmental monitoring stations that could be a way to discover non-marine stations with OMICS capabilities. The ongoing GSC project on global OMICs observatories held a satellite meeting the day following the main meeting to push these efforts forward, so look out for future announcements on this.

Reproducibility and the Dry Lab

Each of the GSC21 “Gold Sponsors” were given a short slot to present relevant work and products to the participants, with Qiagen’s Frank Schacherer giving an overview of their genomics products and tools. This was followed by presentations addressing the challenges of reproducibility in bioinformatics. The enthusiastic Carole Goble (Manchester Uni, UK, and also a member of our Editorial Board) pointed out that most articles addressing this problem cite poor reporting and availability as the root cause, but some also point the finger to flawed design and practices. Carole points out that actually the latter only really becomes obvious when the former is addressed! Wet lab scientists have long been encouraged to provide full comprehensive methods, in contrast Carole argues Dry lab methods are often not as comprehensive as they shoul be, which can lead to insufficient detail to ensure reproducibility. As a means of addressing this issue, Carole presented Research Objects, which is a standardised way to combine bioinformatic entities that form a single object and given a DOI. In principle, this is quite similar to a GigaDB dataset. The Research Object Framework is a set of standards to hold this information. As Carole explained, an important feature is that the data files are not necessarily archived within the Research Object. Rather, the Research Object provides links to the data files and the metadata. Of note, an extension of Research Objects to human data is the BioCompute Object. These incorporate additional standards to promote safe use/reuse of biomedical research, and are currently seeking IEEE approval by the FDA. For more technical details please see the Research Objects website.

Workflows and working hours

The second of the talks in this session was by the newly elected GSC board member Rob Finn (EMBL-EBI, UK) on the use of Common Workflow Language (CWL) at EBI, and in particular the Metagenomics portal MGnify. The title of his talk was “How to get bioinformaticians to do what they were trained to do?” An analysis of his own team at EBI revealed that prior to the implementation of CWL, only 16% of time was spent doing actual new software development. Rob explained that for his bioinformatics team, 47% of working hours was spent data wrangling and maintaining the codebase, 19% on helpdesk, 9% meetings, 2% testing, and 7% on other duties. The implementation of CWL has taken some time, but already it has started to allow a shift of work from the code maintenance to the development of new tools and implementations. The initial phase of MGnify shift to CWL was published in GigaScience, and now MGnify has 7 different pipelines that cover the entire process, and they are able to combine these in docker and deploy on cloud.This enables Rob’s team to distribute computational effort as required.

Rob Finn introduces the Metagenomics portal MGnify at GSC21. Photographer – T Rattei & team. Source – GenSC.org.

Next, Adrian Fritz gave an overview of the Critical Assessment of Metagenome Interpretation, or CAMI challenges. GigaDB hosts the benchmark data and software for the original CAMI study. And we’ve also published their AMBER evaluation package for the comparative assessment of genome reconstructions from these metagenome benchmark datasets. Since then, a second challenge called CAMI2 released additional official challenge datasets, and is now recruiting challengers.

Digital Pathology

The day was rounded off by the keynote speaker Kurt Zatloukal, on the subject of Medical biobanking. He presented work on the uses of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for processing pathology slides to aid in the classification of tumour types. Currently the process is very time consuming and open to human error. The use of AI methods has been shown to be more efficient and enables Clinical Pathologists to focus on the important slides that been preselected by computer algorithms. Although it is early days, the core concept that is being explored here is whether the human expert is only needed to confirm the initial diagnosis provided by the software, thus allowing them the time to focus on the patients and treatments.

Wednesday morning kicked off with Michelle Schorn discussing “Standardising the link between genomics and metabolomics”. In Michelle’s opinion, genomics outputs are very standard (fasta) and the metadata is generally good, but the metabolomics community is less standardised and utilise different platforms with different output formats. These in turn may be variable in terms of metadata content. An additional issue is that metadata are often recorded in disparate ways, and not even recorded with the output. The Q&A’s after this talk put Michelle in contact with EBI’s Metabolight database via Claire O’Donovan who are leading work to federate the exchange of metadata through MetabolomeXchange. This type of standardisation work has been one of the goals of our BBSRC China Partnering Awards grant with EBI’s Metabolights team.

GSC21 working group breakout session. Photographer – T Rattei & team. Source – GenSC.org.

Functional Metagenomics and Genomic Observatories

Jasper Koehorst then woke the otologists in the room with his work on the GBOL ontology which is a method to ensure consistent machine readable functional annotation of (microbial) genomes by statements such as “gene X was predicted in this genome using tool Y and was inferred from genome Z”. These logical statements would benefit greatly from an ontology. Importantly, in place of creating a new ontology, Jasper’s group have incorporated existing ontologies, such as FALDO, PROV-O, SO , SBOL , BIBO, WikiData , FOAF , Gene ontology (GO) and the Evidence ontology, and have extended them to include additional components such as location, i.e. a gene predicted in a genome MUST have a location property. These descriptions are generated as independent RDF triple store databases – 1 per genome – and this means that the only limitation on the number of genomes that can be analysed is storage space and, of course, time. GBOL have also created a tool – Empusa – which can be used to read the ShEx descriptions from the ontologies to validate the data. This also allows comparison of different annotations of the same genome, e.g. for old genomes where the annotations differ to more modern predictions, or the cross comparison

Next Neil Davis (Gump South Pacific Research Station, French Polynesia and GSC board member) reinvigorated the GSC project on Genomic Observatories (GOs). After a few years with little progress. GOs are DNA centric monitoring stations, often but not always co-located with other environmental monitoring observatories around the globe. The founding charter of the GO network was published in 2014 in GigaScience, and now the group are pushing to complete the Minimum Information about Genomic Observatories (MIGO) checklist to enable the standardization and collection of metadata about observatories.

Fascinating as always, Scott Tighe (Vermont USA, and GSC board member) delighted the audience with heroics of collecting extremophiles from far flung places. On the serious side he also pointed out the ground truth for a metagenomic study HAS to be to the organisms that can be cultured from samples. Just looking at the sequence data is not everything! He presented examples where they can readily isolate particular microbes from an environmental sample and sequence that microbe. However when they look at the pure metagenomic sequences from the SAME sample there is no sign of it. Why? Is it sequencing depth? Maybe. But more likely it’s the DNA extraction methods as many extremophiles are immune to most common techniques used to extract the DNA for sequencing.

Before lunch, we then changed tack from genomics and had a session on metabolomics, with 3 speakers all from the EBI (although representing larger collaborations). Maria Martin talked about UniProt and its use of the Gene Ontology for standardized metadata about genes to enable their use in comparative mass spec metabolomics. Claire O’Donovan then described the MetabolomeXchange efforts to standardize metabolomics metadata and made an open call for collaboration to help avoid the difficulties already encountered by the GSC MIxS standards. Keeva Cochrane presented the Enzyme Portal (EP) which is aiming to integrate the masses of data coming from genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics – the latter through UniProt – but also metabolomics data to help elucidate the full molecular pathway from Gene to RNA to Protein to Metabolite.

The conference dinner was kindly sponsored by the City of Vienna, and took place at one of the oldest Heuriger restaurants in the city “Heuriger Marie“. Due to the relatively small size of the conference it was possible to have the keynote lecture at the restaurant before the meal. So in the slightly unusual setting of a back room in an 18th century restaurant, Michael Wagner (University of Vienna) presented his views on “Is predicting function from meta-omics data possible?” After which the wine flowed and discussions went on late into the night.

Michael Wagner skips dinner at Heuriger Marie in favour of delivering a presentation on predicting function from meta-omics data. Photographer – T Rattei & team. Source – GenSC.org.

Biomedical data standardisation will help personalised medicine become reality

The next morning, almost everyone was up for the 9am session focusing on medical genomics. Christoph Bock (Austrian academy of science) chaired and kicked off the session with “Genomic Medicine: The future is now”. His reminder that actually the efficacy of most drugs is less than 25% means that most patients receiving pharmacological treatment are actually not getting the proposed benefits, but are usually still getting the side effects! Christoph ascertained that there are opportunities for entrepreneurial “Direct to consumer” ventures. The analogy he used was that: when public transport was inefficient, Uber sprang up; when hotels and B&B’s were inefficient, AirB&B sprung up. Christoph added that direct to consumer diagnostics would be available now if it wasn’t for the regulations stopping them. Again, a core concept here was that AI can help physicians make more accurate diagnoses. We are aware that genomics is also already being used in many places for diagnosis of cancer, rare diseases and complex diseases, and pharmacogenomics is gaining traction, where genome sequences can be used to aid predictions of efficacy of various drugs & side effects. All these examples can aid diagnosis and potentially guide treatment regimes, but in order to get there we need better access to more standardised data.

Manop Pithukpakom (Siriraj Hospital, Thailand) followed Christophs’ talk with a similar theme, namely the “Clinical interpretation of human sequence variants”. As technology becomes cheaper it’s becoming a more realistic option to sequence the genome of patients to aid diagnosis, but there are many real barriers, one of which is HOW to interpret the massive amount of data provided by genomic sequencing. The (over)simplistic pipeline is sequence, QC, alignment, variant calling, followed by interpretation of variant calls. However, the effect of variants is difficult to predict, partly because we cannot be sure of the structural perturbations of variants. Furthermore, in those rare instances where we do understand the structural consequences of sequence variation, we are not altogether sure how all genes behave in “normal” cells. So we have no confident method to predict pathogenicity of most genes in isolation let alone in more complex transcriptional landscapes. Manop suggested that one means of addressing this challenge was to access data in a more standardised way. However, with different countries having differing healthcare systems and different legislation about data privacy, this goal remains a long way off.

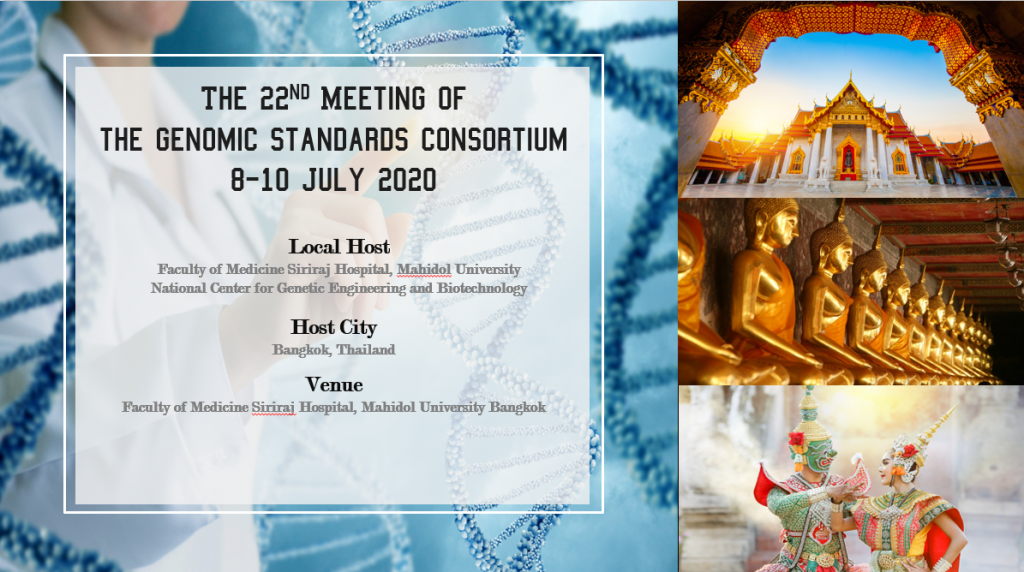

GSC21 ended with the handover to next year’s hosts of GSC22 – Manop Pithukpakom, Yongyut Sirivatanauksorn, and Somvong Trangoonrung. Manop Pithukpakom, who is chair, gave a short presentation to encourage everyone to attend Bangkok, Thailand July 8-10th 2020.

GSC22 is scheduled for July 8-10th 2020 in Bangkok, Thailand