3D imaging of the proteus, a mysterious cave-dwelling salamander

High-resolution images of the head of the blind salamander Proteus anguinus reveal adaptations for life in the dark.

The proteus, also called the “olm”, is a strange beast – locals in the 1600s actually believed it was a baby dragon. In fact a blind salamander, it is snake-like in appearance, colorless, and can live up to 100 years. What intrigues scientists are its adaptions for surviving in lightless caves, where eyes are useless, but an enhanced sense of smell and good hearing are essential for survival.

A new Data Note published this week in GigaScience by an international collaboration, led by Czech scientists Jozef Kaiser and Markéta Tesařová, provides detailed imaging information about the unusual evolutionary features that help the proteus to navigate in the dark.

They used X-ray computed microtomography (microCT) scans to produce stunning 3D reconstructions of the soft tissue in the head of the proteus, allowing them to directly view the changes that have occurred in the salamander over time.

Watch our video abstract here:

Other scientists can now access and use these digital data in their own research, which is particularly valuable given the proteus is endangered, making it hard to get hands on physical samples.

The published article includes colorized 3D reconstructions and easy-to-explore online models (which are also viewable using a VR headset).

A wreck of ancient life

Already the early naturalists were fascinated by this creature of darkness, including Charles Darwin, who described the species as a “wreck of ancient life”. The work in the new GigaScience study using advanced modern-day imaging technology, finally allows centuries-old questions about this strange creature to be answered.

The proteus is the largest cave tetrapod, and the only European amphibian that lives exclusively underground. It is a carnivorous creature, lives off small crustaceans, and swallows its prey whole. Due to living in an underground environment, one of its adaptations is starvation resistance— allowing it to survive up to 10 years without eating. Proteus also has both gills and lungs, unlike most amphibians that as adults lose their gills and move out of the water.

Proteus meets axolotl

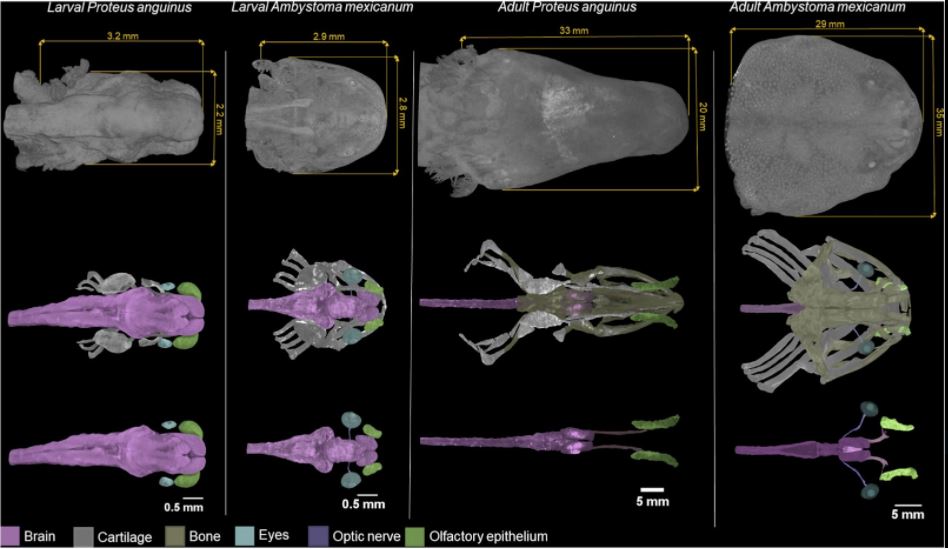

For their research, the scientists used X-ray microCT scanning technology and 3D modeling from multiple samples, including getting images from a closely related surface-dwelling salamander, the axolotl. This provided the researchers with a range of data to assess the changes in the form, shape, and structure of organs of proteus.

The scientists make note of the breadth of analyses these data provided them, saying:

“We accessed several collections to cover developmental stages from larval to adult specimens. Thus, the data can be used to study developmental and evolutionary differences between the stages. Also, making data of proteus and axolotl accessible allow to make an exemplary comparison between cave- and surface-dwelling paedomorphic salamanders.”

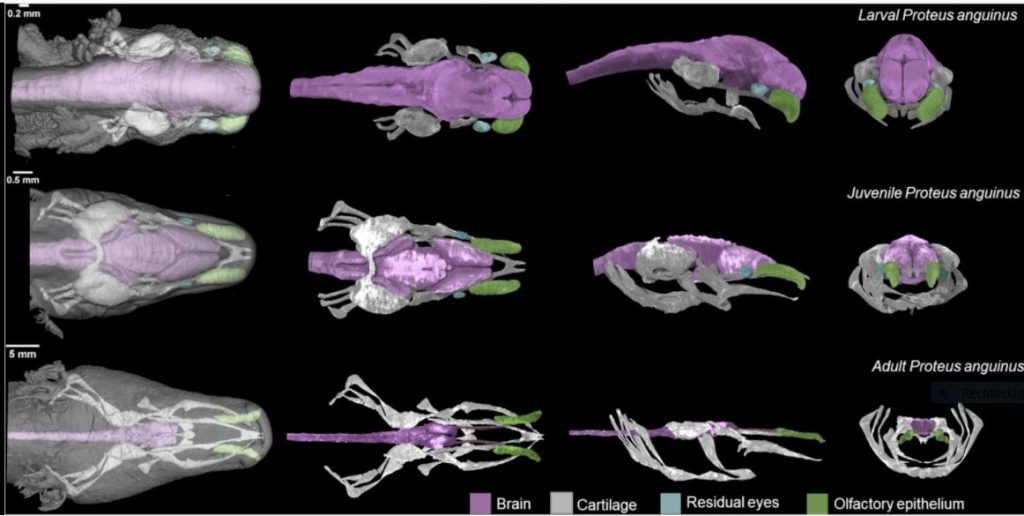

A tale of disappearing eyes

The ancestors of the proteus lived above ground and had functional eyes, but once they began living in lightless caves, selective pressure for retaining vision was gone. The result has been that the proteus’ visual organs are small and incompletely formed, leaving them blind. As a holdover from their ancestors, however, the rudiments of eyes are present in the early stages of life, and the loss of eyes happens during development from juvenile to adult.

Because the data generated by the researchers includes images from both juvenile and adult proteus’ heads, researchers can get far better information about changes of visual development and loss, including changes in position, shape and size as the animal grows into adulthood.

Loss of unnecessary elements is one thing that can happen during evolution, but if survival requires new mechanisms, physical or behavioral changes appear. For the proteus, without vision, other sensory organs needed to change to allow them to obtain food and other resources. To investigate such changes, the Czech research group did microCT scans at different stages of the axolotl to look at different parts of the skull and sensory organs for comparison. The new microCT data and 3D modeling available provide such high resolution, researchers can now get extremely fine details of these changes, rather than more basic changes, such as the proteus odor sensing organ is much larger in the proteus than in axolotl.

Although research using these new data have focused on investigating physical changes, these could also aid in another area of evolution research: investigating behavioral changes important for survival.

Author Lucia Mancini, from the “Elettra Sincrotrone” synchrotron facility in Trieste (Italy), highlights the significance of imaging methods that use electromagnetic radiation (a “synchrotron”):

“The application of advanced 3D imaging technologies can give insights into the living strategies of the proteus. In fact, thanks to the combined use of synchrotron and laboratory-based analyses, future studies could help to model the mechanisms of behavioral adaptation, to better understand the habitat use.”

And her colleague Edgardo Mauri from the Speleovivarium Erwin Pichl concludes:

“The data will allow us to study perceptive abilities through three-dimensional models and to research behavioral responses in relation to chemical cues, auditory frequencies or emission of signals.”

Such studies, as well as providing new basic understanding of how species change over time can improve understanding of evolutionary needs for survival.

Read the GigaScience article:

Tesařová M et al. Living in darkness: Exploring adaptation of Proteus anguinus in 3D by X-ray imaging. GigaScience. 2022 11: giac030. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giac030.

Data available in GigaDB to download (and 3D print): http://dx.doi.org/10.5524/102196

3D models: https://sketchfab.com/GigaDB/collections/salamander

Media coverage:

Gizmodo: https://gizmodo.com/brain-scans-illuminate-weirdness-of-cave-salamander-tha-1848746878