A Flock of Bird Data Comes to Roost

In the long history of humankind (and animal kind too) those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.

In the long history of humankind (and animal kind too) those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.

—Attributed to Charles Darwin

In 1839 Charles Darwin published his famous account of the 5-year second voyage of the HMS Beagle, describing the flora and fauna he encountered surveying South America and circumnavigating the globe, including the famous Galápagos finches that helped develop much his theory of evolution. Providing his descriptions of these species in this 175 year old work, as well as donating his collected specimens to the Zoological Society of London, it was not until 20 years later, in the 1859 “On the Origin of Species” that the true implications of this work was properly laid out and presented. This made Darwin an early pioneer of data publishing, releasing his early observations in the form of a data description very similar to our Data Note articles, before taking the time to analyze and describe it in a full research article.

Over a century and a half on from the publication of this momentous work that gave birth to the field of evolutionary biology, a consortium of over 200 of his academic descendants have now released the largest study to date elucidating the evolution of one of the key branches of the vertebrate kingdom – the Avian Phylogenomics Project. Appropriately utilizing one of the Darwin finch species among the 48 bird genomes studied, as with the plant 1KP project we recently posted about, this data driven work aims to use the genomics of modern birds to unravel how they emerged and evolved after the mass extinction that wiped out their dinosaur ancestors 66 million years previously. With nearly 30 papers published today in journals including Science, GigaScience, Genome Biology, the BMC Series, as well as many more in press, the Avian Phylogenomics Project is just a first step in moves to sequence all 10,000 bird species in a future “Bird B10K project”. These first papers provide details on how birds arrived at their spectacular biodiversity, the evolution of song; how the sex chromosomes of birds came to be; how birds lost their teeth; how crocodile genomes evolved; ways in which singing behavior regulates genes in the brain, and even insight into what dinosaur genomes would have looked like.

P-p-pick up a Penguin (dataset)

GigaScience have published three papers in this Avian genomics series, the most high profile of being timely for the holiday season and the new Madagascar film, the genomes of the Adelie and Emperor penguins (see passionate penguin loving author David Lambert collecting specimens). Using these species as a model for climate change, this study reveals insights into how they have been able to adapt to the cold and hostile Antarctic environment. By looking at how the genomes of these enigmatic and majestic species have been shaped by millions of years of living on the Antarctic ice, this work looks at how they have adapted and survived many previous fluctuations in climate should also provide insight into how recent warming trends may threaten their survival (see the New Scientist take on this topic).

GigaScience have published three papers in this Avian genomics series, the most high profile of being timely for the holiday season and the new Madagascar film, the genomes of the Adelie and Emperor penguins (see passionate penguin loving author David Lambert collecting specimens). Using these species as a model for climate change, this study reveals insights into how they have been able to adapt to the cold and hostile Antarctic environment. By looking at how the genomes of these enigmatic and majestic species have been shaped by millions of years of living on the Antarctic ice, this work looks at how they have adapted and survived many previous fluctuations in climate should also provide insight into how recent warming trends may threaten their survival (see the New Scientist take on this topic).

High Flying Bird Genomes

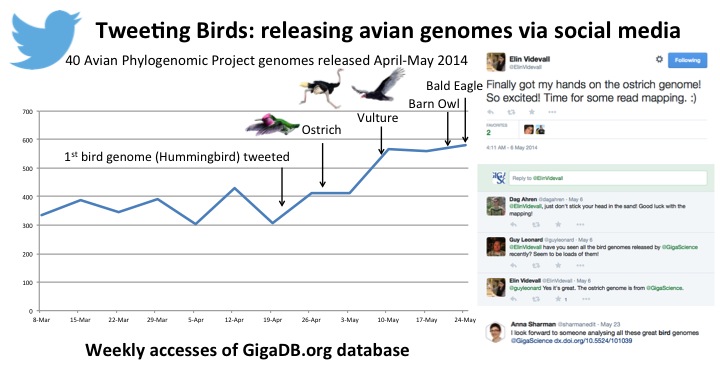

In disseminating the results of these projects, this community of researchers did something similar to Darwin’s model of data release, which was making public all the supporting data from the first stages of the project prior to the publication of the analysis articles. All too often large datasets are held until the publication date of the related analysis paper, due to a variety of reasons. The decision by this community to release these data, in some cases up to 3 years prior to the publications —in 2011 for the aforementioned Adelie and Emperor Penguins, the Pigeon (eventually published in 2013), and Darwin Finch (released in 2012, and as yet unpublished), is a positive, and much needed, move toward providing early access to these data to the broader community. Along with the extra early release of these first species, the remaining avian data for this interdisciplinary, international project came tweeting and twittering out in April and May of this year, to a high-flying response. Releasing a bird a day doubled the traffic to our GigaDB repository, generated many retweets and positive comments from other avian researchers (for example the Ostrich).

Big (Bird) Data

In addition to releasing the data, GigaScience has also published a Data Note that describes the detail and access of the data production for all of the comparative genomics data from the bird species that supports all of these studies. On top of the 4TB of raw data in the SRA repository, we are hosting 150GB of data from all of these assemblies in our GigaDB database, three new crocodilian genomes used for the archosaur genome work, optical maps for the Budgie and Ostrich, as well as the thousands of files used in the phylogenomic work. This has been a massive undertaking for the project manager of much of this work, Cai Li from BGI (pictured), and crediting him as first author of this Data Note gives him the well deserved credit for making these resources more reusable, and the studies more reproducible.

What if I had never seen this before? What if I knew I would never see it again?

—Rachel Carson, author of A Silent Spring

History aside, the bird genomes, affiliated data, metadata, and analyses are especially important today, and for a wide range of areas including evolution, phylogenetics, neuroscience, development, and conservation (discussion of these elements and how it hopes to scale to the Bird10K project are presented in a Commentary also published today in GigaScience from our editorial board member Steve O’Brien). The potential usefulness of these data and analyses for understanding genome evolution and human health is clear, but no less important is its use for conservation. The current crisis of extinction of species (estimated to be 1,000-10,000 time the natural rate of extinction) is as much a danger to the human species as it is to those already disappearing: even if the rapid rate extinction serves as a bellwether (or canary in the coalmine) of the state of affairs in our environment. Birds have the 2nd highest rate of extinction of animal classes. It is 50 years since the death of Rachel Carson who wrote the ground breaking book Silent Spring in 1962, which raised the alarm about the dangerous impact of pesticides on birds —and the environment in general. The book led to multiple advances including a ban on the use of DDT and the formation of the US Environmental Protection agency. Still, 52 years later, the decline in bird species, and all species, continues to accelerate. Hopefully, the rapid and broad sharing of this data will bring to bear the intellectual and physical resources of the entire community to identify biological and physical reasons involved in human and environmental health and sustainability and to develop novel, efficient and cost-effective means to make the necessary changes.

For more see the BGI project portal, the Avian Genomics Series page and the Science special issue page. Scott Edmunds from GigaScience, David Lin from the AAAS, and Guojie Zhang and Tom Gilbert (two of the three project leads) today participated in a press briefing, the recordings of which will hopefully be posted online shortly.

Further Reading

1. Zhang, G; Li,B; Li,C; Gilbert, MTP; Jarvis, ED; Wang, J: Genomic data of Avian Phylogenomics Project. GigaScience 2014, 3:26 https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-217X-3-26

2. Li C, et al.: Two Antarctic penguin genomes reveal insights into their evolutionary history and molecular changes related to the Antarctic environment GigaScience 2014 3:27 https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-217X-3-27

3. OBrien, SJ; Haussler, D; Ryder, O: The birds of Genome10K. GigaScience 2014 3:32 https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-217X-3-32