Publishing Citizen Science data to fight against mosquito borne diseases

Citizen Scientists collect and share enormous amounts of data on invasive mosquitoes from the Mosquito Alert project as part of our GBIF and WHO-supported series on vector-borne diseases.

Just out in GigaByte is the latest data release from Mosquito Alert, a citizen science system for investigating and managing disease-carrying mosquitoes, and is part of our WHO-sponsored series on vector borne human diseases. Presenting 13,700 new database records in the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) repository, all linked to photographs submitted by citizen volunteers and validated by entomological experts to determine if it provides evidence of the presence of any of the mosquito vectors of top concern in Europe. This is the latest of a new special issue of papers presenting biodiversity data for research on human diseases health, incentivising data sharing to fill important particular species and geographic gaps. As big fans of citizen science (and Mosquito Alert), its great to see this new data showcased in the series.

Vector-borne diseases account for more than 17% of all infectious diseases in humans. There are large gaps in knowledge related to these vectors, and data mobilization campaigns are required to improve data coverage to help research on vector-borne diseases and human health. As part of these efforts, GigaScience Press has partnered with the GBIF; and has been supported by TDR, the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, hosted at the World Health Organization. Through this we launched this “Vectors of human disease” thematic series. Incentivising the sharing of this extremely important data, Article Processing Charges have been waived to assist with the global call for novel data. This effort has already led to the release of newly digitised location data for over 600,000 vector specimens observed across the Americas and Europe.

While paying credit to such a large number of volunteers, creating such a large public collection of validated mosquito images allows this dataset to be used to train machine-learning models for vector detection and classification. Sharing the data in this novel manner meant the authors of these papers had to set up a new credit system to evaluate contributions from multiple and diverse collaborators, which included university researchers, entomologists, and other non-academics such as independent researchers and citizen scientists. In the GigaByte paper these are acknowledged through collaborative authorship for the Mosquito Alert Digital Entomology Network and the Mosquito Alert Community.

In one of our Q&A’s we ask first author Dr Živko Južnič-Zonta from the Centre d’Estudis Avançats de Blanes (CEAB-CSIC) in Spain some questions about this work.

Tell us about the data being presented in the paper?

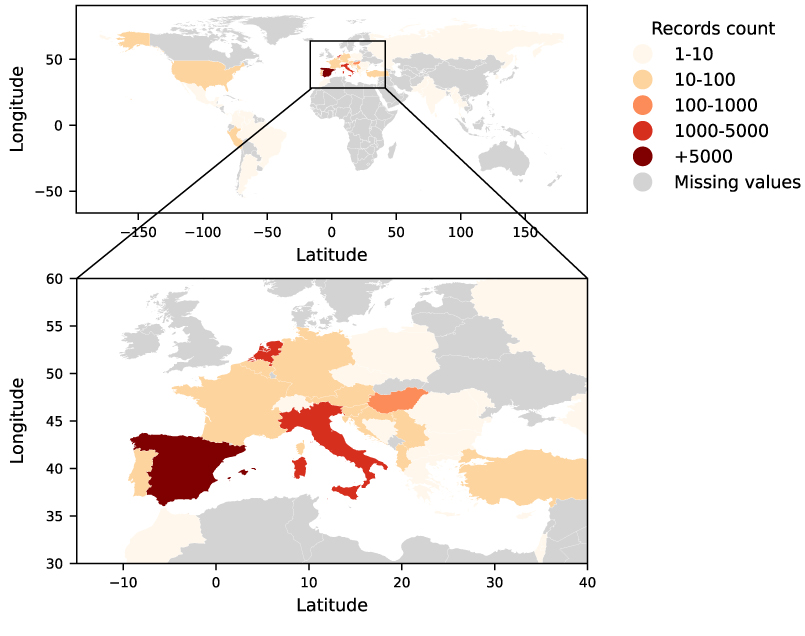

The Mosquito Alert dataset published on GBIF includes occurrence records of adult mosquitoes collected by citizens through the Mosquito Alert smartphone app. Each record is linked to a photograph which is validated by entomological experts to assess its species. The temporal coverage of the dataset is from 2014 through 2021 and the spatial coverage is worldwide. Most of the records from 2014 to 2020 are from Spain, while starting from 2020 the coverage increased in Europe, mainly in the Netherlands, Italy, and Hungary. Mosquito Alert is now a mature near-real-time surveillance system of five targeted disease-vector mosquito species of concern in the EU.

Were there any particularly interesting or unexpected findings that have come from this Mosquito Alert data?

From a surveillance perspective the system has been able to detect many appearances of Aedes albopictus much beyond its immediate expansion front, like in the Spanish Autonomous Communities of Andalucía and Aragón, which happened as well within other EU countries. A major highlight was the first detection in 2018 of Aedes japonicus [the Asian bush mosquito] in Spain, an isolated population located at a whopping 1,300 km distance of its nearest known location in Europe. This species was not expected to appear and thus was not targeted by any existing surveillance; later up to 2020 the system also collaborated to assess the distribution area of the species across Northern Spain which was actually much broader than estimated in 2018. As a biodiversity feature, the expert validators have labeled as many as 28 autochtonous Culicid species throughout Europe in only two years. These are only indicative suggestions because relying only on photographs, although in some cases where field confirmation was possible, they led to publication of distribution articles broadening known distribution of autochtonous species.

What have been the challenges in sharing it?

Finding the right format of author citation and setting up a credit system to evaluate contributions from multiple and diverse collaborators.

Fulfilling the required and recommended metadata fields in order to build the GBIF occurrence dataset and automatize data and metadata generation to ease future dataset update.

What do you hope others will do with it?

- Perform data augmentation and calibration in mosquito distribution models.

- Perform risk assessments, like characterization of critical areas and seasonal variability for disease risk transmission.

- Mosquito images can be used to train machine-learning models for mosquito detection and classification.

- The Mosquito Alert dataset published in GBIF is updated annually and thus could be used for early warning of invasive species across scales, from city to continental scales.

- The Mosquito Alert dataset published in GBIF is a subset of the row public dataset that is openly shared and updated daily on the Zenodo repository. The Mosquito Alert Data Portal provides metadata of this row dataset called reports. Because of its daily update, this dataset could help to optimise vector control, as citizen scientists provide information about nuisance and presence of mosquitoes at almost real time.

Further Reading

Živko Južnič-zonta, Isis Sanpera-calbet, Roger Eritja, John R.b. Palmer, Agustí Escobar, Joan Garriga, Aitana Oltra, Alex Richter-boix, Francis Schaffner, Alessandra Della Torre, Miguel Ángel Miranda, Marion Koopmans, Luisa Barzon, Frederic Bartumeus Ferre, Mosquito Alert Digital Entomology Network , Mosquito Alert Community, Mosquito alert: leveraging citizen science to create a GBIF mosquito occurrence dataset, Gigabyte, 2022 https://doi.org/10.46471/gigabyte.54

Read the other papers in the series as they are published here: https://doi.org/10.46471/GIGABYTE_SERIES_0002